Optimizing Bandoneón Practice When Time is Short

Strategies to Perfect Bandoneón Practice There are times when musicians simply can’t dedicate as much time as they’d like to practicing, refining their skills, or

Anyone familiar with the bandoneon often encounters the magical number: 442. When we say that the bandoneon tuning is 442, this value represents the frequency in Hertz of the central A that serves as a reference point for tuning all the other notes of the bandoneon.

If you’ve ever wondered why this precise value instead of a nearby one like 443 or 441, you’re in the right place. Despite my extensive research, I haven’t been able to find a specific reason. However, what I’ve discovered is a fascinating story that will deepen your appreciation for this unique instrument.

Before going to the topic, I want to emphasize the importance of supporting my work and research by subscribing to the newsletter for updates on new publications. I highly recommend subscribing to my YouTube channel as well, where I regularly share videos containing technical information about the bandoneon, lessons, and musical insights. Your support and participation are crucial to continue creating quality content. Thank you in advance for your support!

The bandoneon is not an instrument that can be tuned as easily as a guitar or a violin. The desired vibration frequency is achieved by filing the reeds, a task that requires specialized skills. Everyone knows that the internationally standardized value for A is 440 Hz. However, the bandoneon is commonly tuned two cents above this reference, at 442 Hz. But why this discrepancy? My research followed two main lines of inquiry, an orchestral explanation and an acoustic explanation.

Ancient bandoneons freshly out of the factories in Germany were tuned according to the NA (Normalen Abstimmen), with A at 435 Hz, and upon reaching Argentina or Uruguay, they were tuned again upon the musician’s request.

It is well-known that the international standard for A at 440 Hz was adopted quite late, more or less after World War II. As for Argentina and particularly tango, it seems that some orchestra conductors adopted the practice of tuning their musical formations to 440 because they also performed in the United States, where the international standard was already established.

Argentinian orchestra conductors adopted this practice and introduced it at home, thereby also compelling the bandoneon to raise its tuning because the instrument was the reference for all the other instruments, along with the piano (the two instruments in the orchestra that couldn’t be tuned “on the spot”).

With this explanation, I clarified why the bandoneon, upon arriving in Argentina, shifted from the factory tuning of 435 Hz to a value equal to or higher than the international standard of 440 Hz. But why did the fixed value of 442 specifically consolidate for the bandoneon?

In reality, it was (and still is) quite common for the piano to be tuned to 442 or 443 Hz. Therefore, since the piano and the bandoneon were the reference for all the other instruments in the orchestra, the bandoneon might have simply inherited this frequency.

But perhaps there’s more to it. We must consider some specific technical aspects of the bandoneon, particularly its characteristic of producing sound through reed vibration.

All reed instruments tend to drop in pitch when played forcefully; in the bandoneon, this phenomenon is particularly pronounced and can sometimes reach differences of a semitone. I had always observed this phenomenon, so I thought the two-cent difference was to compensate for this frequency drop.

Although I didn’t find mention of this explanation in any of my sources, I found a similar explanation in this article. In practice, having to bring the bandoneon from the factory value of 435 to 440 Hz forced tuners to raise the frequency of the reeds, which is achieved by removing metal, an irreversible process that can only be done a limited number of times. The price to pay for a higher frequency is a less stable reed with a tendency to drop, thus necessitating an increase in frequency with each new tuning.

However, a spontaneous question arises: what about when the bandoneon wasn’t played loud? Did it still drop in pitch? This explanation leaves me somewhat perplexed. So I found another explanation that seems more plausible.

According to this article, the bandoneon tuners Romualdi and Fabiani explained the two-cent difference in Hertz more than the standard because it allows the harmonics of the instrument to stand out to the maximum, but such a small difference wouldn’t be significant in terms of intonation. The result would be a tuned but brighter sound.

It seems strange to me that two great connoisseurs of the bandoneon like the aforementioned Romualdi and Fabiani avoided talking about such a significant issue as that of the pitch. Obviously, the pitch drop wasn’t a valuable reason. However, the explanation attributed to them also leaves me somewhat unsatisfied.

Therefore, I believe that behind the need to raise the bandoneon’s tuning to compensate for the continuous removal of material from the reeds, there may be a grain of truth.

It’s likely that with the bandoneon, necessity turned into virtue: the real problem of metal removal from the reeds following frequent tunings inadvertently forced orchestras to tune slightly higher each time, either because the orchestra was compelled to tune with the bandoneon, which couldn’t be tuned, or because in this way, it is said that acoustic tensions with the piano and violin were accentuated.

Truth or legend, this phenomenon was given the name afinación brillante (bright tuning), and it was consciously sought after by orchestras and musicians.

Additionally, according to legend, a high tuning forced the bandoneonist to play only with a certain orchestra: in fact, his instrument, now brought to very high frequencies, could hardly be lowered again without permanently damaging the reeds, and in this way, the orchestra conductor who imposed a high frequency earned the fixed and stable presence of the bandoneon player.

In fact, it is very easy to find instruments tuned to 445 Hz, or even higher frequencies, in Argentina.

It’s difficult to come to a single conclusion because there are no true testimonials, and as often happens with the bandoneon, personal opinions turn into myths and legends, often contradictory and irreconcilable.

With this article, I tried to unify some different possible interpretations. My personal conclusion is that the habit of the afinación brillante, combined with the need to approach the universal standard reference of 440 Hz, led to a moderately higher tuning, maintaining the brilliance of the instrument without giving up the possibility of playing with any formation.

So the magical number 442 was a valuable response to a series of issues and over time simply became a convention.

Strategies to Perfect Bandoneón Practice There are times when musicians simply can’t dedicate as much time as they’d like to practicing, refining their skills, or

The project Duruflé meets the Bandoneón proposes an innovative exploration of the music of the great French composer Maurice Duruflé through the bandoneón, an instrument

In this bandoneón tutorial I explain the first of a series of preparatory exercises. After having dedicated a series of videos to the fundamental aspects

Learn about chromatic bandoneons! Download FREE PDF keyboard layouts for Peguri, Manoury, & Crosio-Caliero systems. Unisonoric bandoneon explained for beginners.

A Lesson from the Bandoneon to Move from Stage Panic to Expressiveness 2024 is coming to an end and I have been very busy during

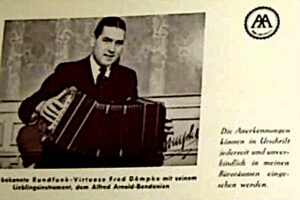

Who is Fred Dömpke and why should deserve more consideration among the bandoneon players? The bandoneon is conquering a significant role in jazz. Many bandoneon